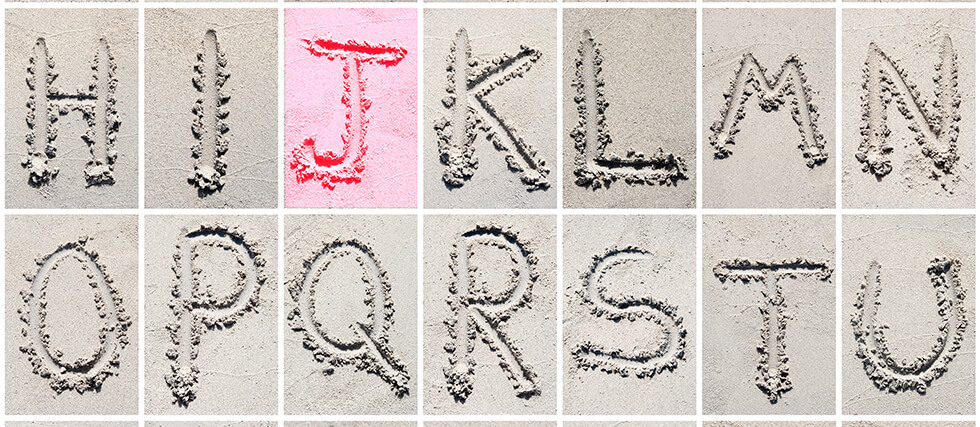

‘J’ Was the Last Letter Added to the Alphabet

For centuries, the letter “I” had to pull double duty. It represented both the vowel sound we know in words like “it” and the consonant sound at the beginning of words like “jar.”

In the 16th century, an Italian scholar named Gian Giorgio Trissino decided enough was enough. He argued that these two sounds were distinct and deserved separate letters. He proposed using “I” for the vowel and a modified version, “J,” for the consonant.

It wasn’t an overnight change. Even after Trissino’s proposal, it took a while for “J” to catch on. Early adopters were mostly in Romance languages like Italian and French.

One of the most significant moments for “J” in the English language was the 1629 revision of the King James Bible. This was one of the first major English texts to consistently use “J” as a distinct letter. This helped solidify its place in the alphabet.

Now, of course, “J” is a vital part of our alphabet, used in countless words and holding its own unique place in the English language.

So, while “Z” might bring up the rear, “J” was the last to truly join the alphabet club.

Which letter was first? Probably “A.” We think.

While it’s hard to say for absolute certainty which letter came first, “A” is generally considered the earliest addition to the alphabet.**

Here’s why:

The ancestor of our alphabet, the Proto-Sinaitic script, emerged around 1850 BC. The first letter in this script represented an ox head (called “aleph” in Phoenician) and made a glottal stop sound (like the catch in your throat before saying “uh-oh”). This evolved into the letter “A” and its sound.

The Greeks adapted the Phoenician alphabet, and their first two letters, “alpha” and “beta,” gave us the word alphabet. “Alpha” directly descends from the Phoenician “aleph.”